Flying blind to MNPI

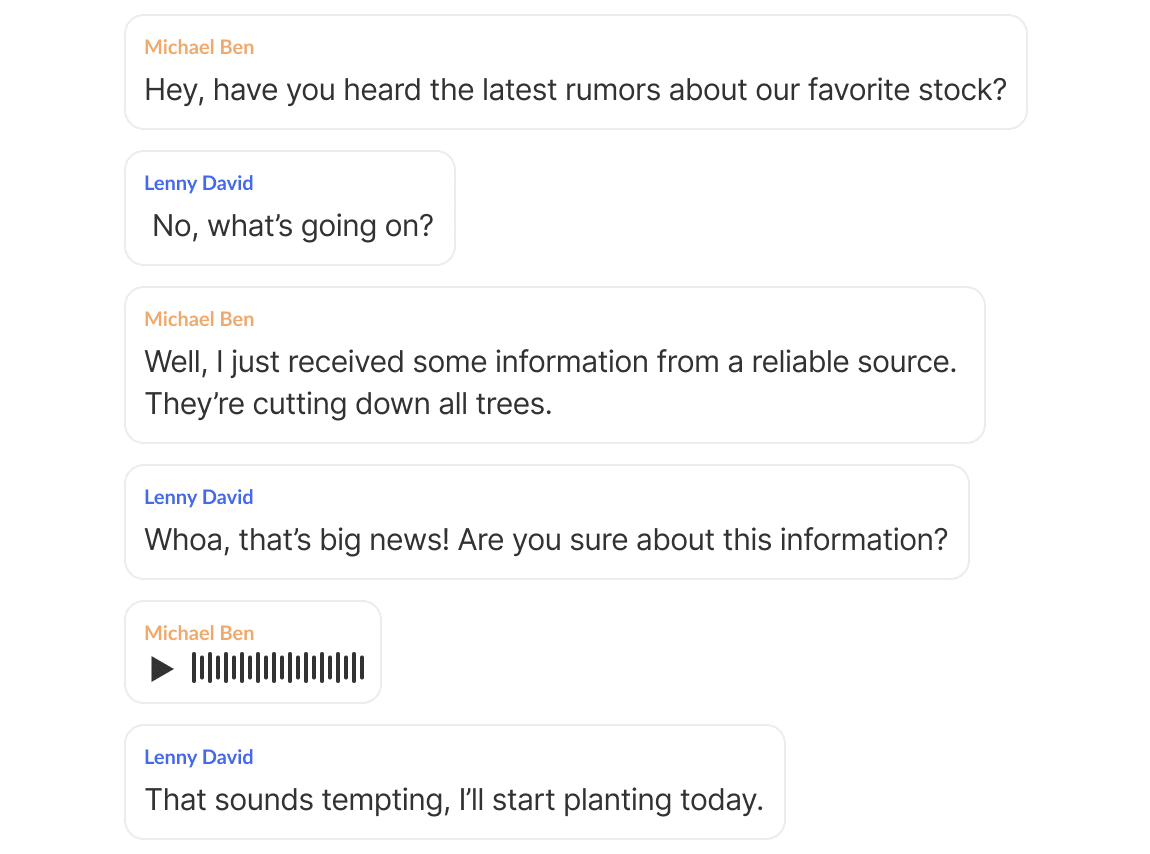

Current manual processes for managing MNPI are labor intensive, time consuming, and don’t uncover where real wall crossing is happening until it’s too late.

- Zero visibility on MNPI breaches

- No way to demonstrate ethical wall integrity

- Late violation discovery

Only the right eyes on every communication

Turn reactive protection of into proactive prevention by automatically monitoring every conversation with a powerful AI detection system.

- Pinpoint the MNPI breach moment

- Identify infractions early and take action

- Fully monitored ethical walls